Always the other, I thought as we broke into Rafter’s black box of a studio. On the fire-escape, fifth floor, shabby part of town. Moonlight our only witness. His wife looked beautiful in it. Desert skin pressed against forbidden corners of the night. Rafter Sousa never allowed either of us near this hole. His artistic refuge, his muse asylum, his place to be important.

“Screwdriver,” I said.

“You’re good at this,” Maria whispered. “Break into apartments often?”

“Once a week into my own,” I admitted. “Always forget the key.”

Rundown, inimitable buildings all around. Metallic power-lines engraved onto a dark sky. The noise of young boys laughing, nothing to do with us, kicked cans, subway in the distance. Calm, beautiful night in a strange part of town.

Maria Sousa looked exhilarated, youthful, innocent for a moment. I held her by the belt-noose in her jeans. Brushed the ink black hair from her eyes. Our mouths met with the frenzy of amateur criminals. Her lips cold in the summer night. I took her again, my hands on fire against the winters of her waist. I couldn’t tell which of us flinched first. Her, because she was kissing me outside her husband’s studio. Or me, because I thought for an instant I saw him inside, waiting.

“This is wrong,” Maria said. “Right now it’s very wrong.”

“I know,” I said. “That’s what we have.”

Penny on a golf-course. Standing in for the one who’d gone away. Had I become a place holder for Rafter Sousa? She’d kiss him and smile. She’d kiss me and try not to fall apart.

“I’d forgotten why we came,” I acknowledged. “For a second I thought it was just you, me and the weather.”

“We should get inside before someone notices.”

I got back to turning screws. Same repeating motions. Tried to ignore the memories of her skin. Couldn’t get ways to touch her out of my head. Reasons that stood in the way.

Rafter Sousa was eccentric in subtle ways. He was an artist after things he couldn’t name. A miner of half-lit theories cut from the night. His faults seductive, themselves almost art.

Maria was an editor; clever, audacious, always on the verge of tears or beauty. Would speak among strangers, give you a nickname and yell it to the world. Soft Moroccan skin with L.A. education. Polish eyes deep like a wolf’s.

I filled the spaces between. Somewhere between her legs and his artistic expressions.

It was inevitable, I suppose. Forever a step behind Rafter Sousa. I laughed at the same jokes the following day. If he’d found ways to love her it was only a matter of time before I would.

I could’ve been happy, under different circumstances. Penny in love, fucking some poor bastard’s wife. But I respected Rafter too much, the way boys admire pirates and divorced men. A sense of rebellion tinged with indifference that seemed always distant, impractical. He smoked cigarettes while I died of cancer.

The final screw slipped from her fingers and dropped loudly through the cracks. Sudden screech of a window from above, like fingernails across the moon. A shadow peered down at us.

“That you, Sousa?”

I froze. Maria nudged my side, solicited me to be him.

“Yeah, it’s me,” I imitated nervously. “Forgot my key.”

“At least it’s a nice night,” the shadow said.

“At least.”

“Night, Sousa. Try not to wake the whole fucking neighbourhood.”

“Right, sure. Goodnight, Jim.”

I unhinged the window and we snuck inside. Together immediately looked back through the broken frame. We’d infiltrated Rafter’s most private space. Inside, dark and abandoned.

“Jim?” she said. “How’d you know his name was Jim?”

“I panicked,” I said.

“So you just made up a name!?”

“I panicked! Besides, a wife breaking into her husband’s place,” I reasoned. “How much trouble can we get in?”

“I’d rather not find out,” she said.

We still hadn’t called the police. It’d been three weeks, no word, no trace. Rafter disappeared frequently for days at a time. He’d wander back from some random town or mountain – unkempt, re-inspired, eager to draw, drink and make love.

“Artists have to vanish from the world to cherish it,” he once said.

But this felt different, ominous. It was the first time he’d disappeared since the beginning of my affair with Maria. I wasn’t sure what he knew. That I’d followed him down the long lines of her skin. That a letter spoke of Northern Africa and a Warsaw hospital bed.

Strange forms of disclosure haunted my dreams. I imagined Rafter confronting me in alleyways. I imagined Maria whispering, “it’s over.” Guilt and desire were a slip of the tongue for weeks. Maria and I spent anxious nights together, entangled. Our love-making had been reckless and imperfect. Addicted to the taste of weakness and remorse on each other’s lips.

We’d made love in his house, but tonight, in his studio, she was pushing me away.

“I should hate this place,” Maria said. “But it’s him. It’s cluttered and beautiful like him.”

Beautiful, in a heartbreaking way. Intense, self-indulgent, self-destructive. Altogether too dark, too desperate. Abstract obsessions in art. Flesh too close to candle-light. The drip and slow drying patterns of red wax. Beautiful maybe, but not essential. Not like her.

“It’s not worth what it cost,” I said.

Her eyes had a way of turning, quick and deep like a knife. She glanced sharply through built-up layers of the past. I could never tell if she meant reproach or invitation.

Rafter Sousa was never very good. He was brilliant, but never very good. He garnered an audience. His strange comics sold well enough to do it for a living. That should’ve been enough for someone who could barely draw. He wasn’t good enough to support a home and a separate studio. Maria was furious that he just went ahead and signed the lease. Unpaid bills and missed vacations.

“Art comes from brooding,” I remember him telling her in front of me. “I can’t brood properly with you around. I need a place to myself, something empty, no distractions.”

“You need a new argument,” Maria said. “You keep playing the same cards, and I keep waiting for you to grow up. We have bills, love. We have a marriage, I think. You can’t keep ignoring these things and blaming it on art.”

Yet she always put up with it. She put up with wandering nights and neurotic behaviour. She put up with a studio they couldn’t afford and that she couldn’t touch because Rafter was convinced that he needed a dark, secluded place to accomplish his ideas. The artist in him would’ve withered without it, and in the end it was the artist she loved. She fought, scathingly, convincingly, knowing full well it was only to concede. I both relished and resented that they felt able to bicker openly in front of me. Manifestations of their difference broke like sudden thunder and I’d find myself caught in the fascinations of a storm. They were a couple that infuriated each other to the point of nudity and forgiveness. I’d stand there, awkward and intrusive, silently sipping Earl Gray while pondering things I’d say in his place.

Eventually Maria became his duty and the tiny studio became his home. At first she was convinced he was cheating on her, using the studio as some excuse and cheap motel. But after enough weeks it didn’t matter. She’d lost him to something else, maybe another woman, probably just art. That’s when I kissed her. The day she realized she’d become someone’s obligation. It was a cloudy Sunday with chance of showers. The Knicks had lost again. And with tears streaming down her cheeks I kissed Maria Sousa, and I remember it was perfect.

We glanced around the single room. Bookshelves, pencil-shavings, empty power-bar wrappers. A mini-fridge with Chinese take-out and bottles of wine. The apartment reeked of him. Soy-sauce and marijuana in the air. Hints of masochism on the sheets. Sharp knives and an odd number of chopsticks in the drawer. There was a faint sense of hope in the scattering of things. A well lit table in the corner. The only bulb in the room. Everything else was darkness. Even the fridge remained black when you opened it.

On the glowing table was a manuscript for Rafter’s new graphic novel. Over three hundred pages of intricately crafted panels. Neither of us had seen it yet. His great project, his fixation of the last few months.

“His fucking mistress,” Maria said.

It looked clean, finished. Except no words. No scribbled dialogue, no titles, nothing that remotely resembled language.

The graphic novels were Rafter’s creations – his ideas, his pictures, his story. In early drafts he’d include basic dialogue, just so I knew what he was after. But for the most part he left writing to me. Maria edited. It was always our names in small print below his.

You could see it in Rafter’s eyes and in the trembling of his lips. Wild but vague. Leaning there on the precipice of his unformed thoughts, that one perfect thing. I imagined a forgotten word on the tip of Rafter’s tongue. For weeks he didn’t dare kiss her for fear of swallowing and pushing it further away.

But I knew it wasn’t a word. He was after something else. Remnants of our sunken ship.

“I’ll get it out,” he kept repeating, “I’ll tell it to jump, I’ll shove the fucker if I have to.”

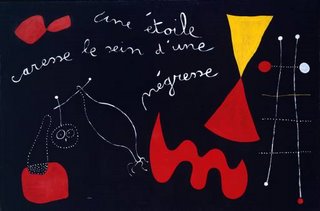

I was drawn by his obsession, desperate to play a part. But Rafter had created his masterpeice without us. I began to flip through the burnt sienna pages:

Film-noire atmosphere.

Confrontation of styles and figures in alleyways; conversations without words.

Cryptic self-portraits.

Moments of oil-based abstraction.

Furious bodies raging against claustrophobic quarters.

Human limbs trapped in paranoid pencil strokes.

The art was better than anything he’d ever done.

Maria and I sat down together at the table. Stared silently at page 88, centrepiece in this museum of misplaced shadows. I poured two glasses of wine.

“To the webs we weave,” I suggested.

She responded with a look of reproach or invitation. Tonight she’ll bite her lip in the room he denied us. Our glasses touched timidly. Exaggerated faltering in everything we did. The wine was strong. Warm, like the night.